Contents: #12 Mg, #25 Mn, #38 Sr, #39 Y, #48 Cd, #65 Tb, #67 Ho, #68 Er, #69 Tm, #70 Yb

In 1787 a previously rare mineral was obtained in quantity from the lead mine at Strontian, Argyleshire, Scotland. In 1790 an Irish physician, Adair Crawford (1748-1795) found the strontianite was more soluble in hot and cold water than similar barytes. In 1791-1793 Dr. Thomas Hope, professor of chemistry in the University of Edinburgh found clear distinction that the mineral contained a new earth which he called strontia. Hope noted that strontia slakes even more avidly with water than does lime, that its solubility in water is extremely great, that unlike the green color barytes give a flame and the red of calcium, strontia tinges the flame a more brilliant red, and finally, while the properties are intermediate between those of lime and baryte, it is not a combination of the two. Hope, who drew large audiences to his chemical lectures and demonstrations, had learned Lavoisier's views and imbibed the atomic ideas of John Dalton. According to Lavoisier, each distinct earth contained a distinct element. In 1808 Sir Humphry Davy isolated the metallic element by the electrolysis method he had developed for Calcium and Barium. The element within the earth strontia was called Strontium (Sr = #38).

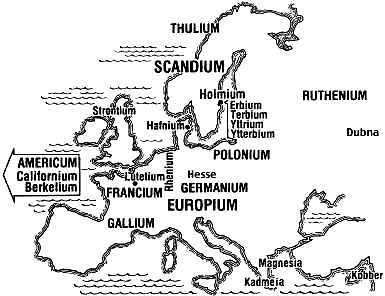

The following elements were discovered in earths separated from the dense, black mineral gadolinite (earlier called ytterite) found in the mine at Ytterby, a village near Stockholm, Sweden.

The following elements were discovered in earths separated from the dense, black mineral gadolinite (earlier called ytterite) found in the mine at Ytterby, a village near Stockholm, Sweden.

Yttrium (Y = #39) was named for its earth yttria by Gadolin.Erbium (Er = #68) was named for its earth erbia by Mosander.

Terbium (Tb = #65) was named for its earth terbia by Mosander.

Ytterbium (Yb = #70) was named for its earth ytterbia by Marignac.

Holmium (Ho = #67) and its earth holmia were named for Holmium, the ancient name for Stockholm.

It and Thulium (Tm = #69) were isolated from erbia by Cleve. The earth thulia was named after Thule an ancient name for Scandinavia.

In 1817 Dr. Friedrich Stromeyer (1776-1835 at right), as part of his government duties that accompanied his professorship of chemistry and pharmacy at Göttingen University, inspected Hanover apothecaries. He found one substituting zinc carbonate for zinc oxide. Visiting the manufactory at Salzgitter, he was told that heating their zinc carbonate read hot to produce the oxide left an uncharacteristic yellow color similar to iron even though no iron was present. Soon after he was sent a sample produced elsewhere that falsely seemed to contain Arsenic. Examining both, Stromeyer formed a carbonate which was not soluble in excess ammonium carbonate solution. After filtering, he formed the oxide by heating, and reduced it to a bluish gray metal with a bright luster. Because the metal was associated with Zinc, he called it Cadmium (Cd = #48), meaning cadmium fornacum or furnace calamine. Calamine (ZnCO3) was an earth found in Kadmeia in Ancient Greece.

In 1817 Dr. Friedrich Stromeyer (1776-1835 at right), as part of his government duties that accompanied his professorship of chemistry and pharmacy at Göttingen University, inspected Hanover apothecaries. He found one substituting zinc carbonate for zinc oxide. Visiting the manufactory at Salzgitter, he was told that heating their zinc carbonate read hot to produce the oxide left an uncharacteristic yellow color similar to iron even though no iron was present. Soon after he was sent a sample produced elsewhere that falsely seemed to contain Arsenic. Examining both, Stromeyer formed a carbonate which was not soluble in excess ammonium carbonate solution. After filtering, he formed the oxide by heating, and reduced it to a bluish gray metal with a bright luster. Because the metal was associated with Zinc, he called it Cadmium (Cd = #48), meaning cadmium fornacum or furnace calamine. Calamine (ZnCO3) was an earth found in Kadmeia in Ancient Greece.

Magnesium (Mg = #12) has long been known. In the drought of 1618 Henry Wicker noted thirsty cattle would not drink from a water hole on the commons at Epsom, Surrey. Epsom's salts were distinguished from other salts and became a fashionable spa for their healing effects on sores. In 1755 Dr. Joseph Black (at left) of Edinburgh distinguished quicklime from magnesia alba,

Magnesium (Mg = #12) has long been known. In the drought of 1618 Henry Wicker noted thirsty cattle would not drink from a water hole on the commons at Epsom, Surrey. Epsom's salts were distinguished from other salts and became a fashionable spa for their healing effects on sores. In 1755 Dr. Joseph Black (at left) of Edinburgh distinguished quicklime from magnesia alba, the white magnesia

(MgCO3) from Magnesia in ancient Greece. He noted the loss of weight during calcination when fixed air (CO2) was expelled. Humphrey Davy first isolated the metallic element by electrolysis in 1808. Davy proposed the name Magnium to avoid confusion with Manganese, but Magnesium persisted.

A dark brown half mineral

from Germany called braunstein was known to color glass and pottery violet. It was also known as magnesia nigri meaning black magnesia

(MnO2) from Magnesia in ancient Greece. In 1770 Bergman distinguished it from lime and magnesia alba, described it as the calx of a new metal, but failed to reduce the ore. In 1774 a friend of Bergman, Carl Scheele completed a three year investigation, called it Manganese (Mn = #25), and described it as the calx of a metal different from any then known. Johan Gottlieb Gahn (1745-1818 at right) finally isolated Manganese as an element. When his father died early, Gahn had gone to work on the lowest and wettest level

of mines, becoming an expert at the blow-pipe which he carried with him everywhere. The young Berzelius, who eventually became one of the most influential chemists, once watched with wonder and admiration as Gahn use his blowpipe to produce a speck of copper from a quarter sheet of paper. In 1774, Gahn fired a crucible lined with moist charcoal containing an oil and ore mixture in the center. He obtained a button of metallic manganese weighting about a third of the original ore. Gahn later became the accessor at the College of Mines, and owned and managed mines and smelters including the sulfuric acid plant where Berzelius discovered Selenium. Gahn supplied pure Copper to the Americans for sheathing ships during their revolution. While he recorded little of his accomplishments, his Swedish hospitality and his zeal for science were renown.

![]()

| introduction | alchemy | planets | other celestial objects | color | other properties | myths | people | minerals | other places | combination names |

| to site menu | Introduction to Development of Periodic Chart |

18th Century vocabulary, & index of people |

chemistry | physics | ||||||

| created 31 December 2000, amplified 1 April 2001 latest revision 26 June 2007 |

by D Trapp | |||||||||